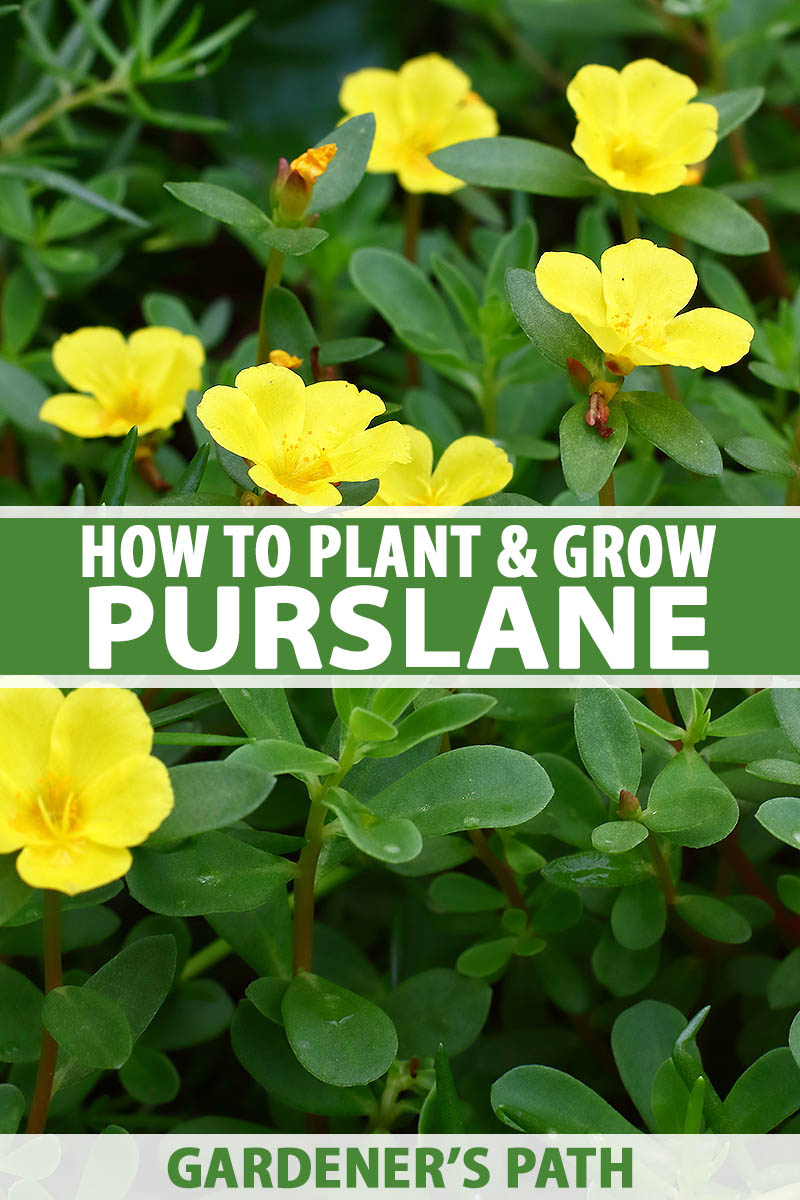

How to Plant and Grow Purslane

Portulaca oleracea

When I told my husband I was planting purslane in the garden, I suspect he thought I’d lost my mind.

No doubt he was thinking back to the years when I fought furiously to tug the tenacious weed from my garden beds.

These days, I know better. Portulaca oleracea is a delicious, versatile green that – as you might have guessed, given that it’s considered a weed – practically grows without any help at all.

Did I mention that it’s incredibly good for you, too?

Writer Michael Pollan even described it as one of the two most nutritious wild edible plants, along with lamb’s quarters, in his book “In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto.”

In Defense of Food, Available on Amazon

You can grow purslane year-round as a microgreen, and all summer long as a vegetable.

In fact, you might find the hardest part of cultivating this tangy green is keeping it from growing a little too well.

There are lots of things you can do to ensure a rewarding harvest, including selecting the right time of day to pluck the leaves for the best flavor.

You’ll also need to know how to use the greens once you’ve harvested them, so let’s dive in.

What You’ll Learn

What Is Purslane?

P. oleracea is an annual succulent that has been considered both a useless weed and a powerful medicinal plant at different times throughout history.

Also known as little hogweed, pigweed, fatweed, and pusley, it’s gained recognition in US popular culture more recently for being a nutritional powerhouse.

Purslane contains lots of antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals – it even has seven times more beta carotene than carrots.

The Portulaceae family also includes the ornamental wingpod purslane (P. umbraticola) and moss rose (P. grandiflora). Rather than being grown for food or medicine, these species are often cultivated for their flowers.

The perennial wingpod type has green, rounded leaves, reddish stems, and yellow blossoms while the annual moss rose is a desert plant, often with spiky leaves, that may produce flowers in a variety of colors.

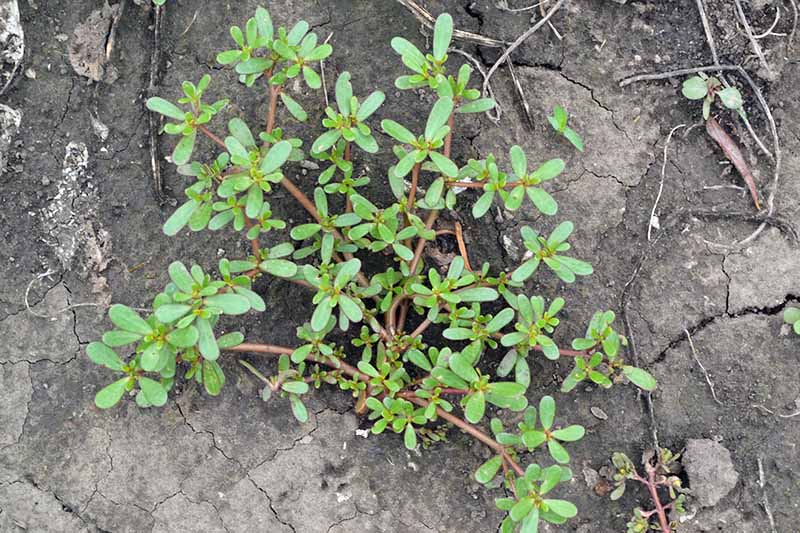

Common purslane, on the other hand, looks a little like a tiny jade plant, and you can eat the leaves, stems, flowers, and seeds, either raw or cooked.

The leaves taste slightly citrusy and salty, with a peppery kick not unlike arugula, but with a juicier crunch to it.

Its small yellow flowers have five petals and yellow stamens. The plants blossom from midsummer through early fall, at which point the flowers are fertilized and then produce seeds.

Not everyone is as big a fan of this nutritious green as I am.

The United States Department of Agriculture calls it a “noxious weed,” and in some regions its cultivation is limited or prohibited.

Don’t let that put you off (unless you have reason to, depending on where you live!).

Purslane is also widely considered a “superfood” that’s popping up in fine dining and farm-to-table restaurants across the country.

Cultivation and History

P. oleracea has naturalized in most parts of the world, from north Africa and southern Europe, where it likely originated, to North America, where there is evidence that native people across the continent were cultivating and foraging for it long before Europeans arrived.

Historically, it was cultivated in central Europe, Asia, and the Mediterranean area.

You can also forage and eat the wild stuff, which tends to be more pungent and intense in flavor.

I think cultivated purslane has a less bitter, sweeter flavor. Cultivated plants, which grow in USDA Hardiness Zones 5-10, usually have larger leaves and grow in a more upright form. That’s handy, come harvest time.

Propagation

Purslane is typically propagated from seed, but you can also grow it from stem cuttings, divisions, or transplants.

You may have a hard time finding seeds or plants at your local nursery, however.

From Seed

If you buy purslane seeds to get started, you’ll likely never need to buy them again, since one plant can produce over 50,000 seeds through the course of its lifetime.

You can direct sow this vigorous green outdoors, after the last frost has passed and soil temperatures reach about 60°F.

Sprinkle seeds onto moist soil and press them in lightly. Don’t cover them, as they need light to germinate. Seedlings take seven to 10 days to sprout after planting.

Once they’ve sprouted and have formed a few true leaves, thin them to 8 inches apart.

You can also start seeds indoors at least three weeks before the last frost. Transplant them after they’ve grown one set of true leaves and all risk of frost has passed.

Be sure to harden them off for a few days before planting them out in the garden.

To do this, put them in a sheltered area like a patio, and gradually expose them to an additional hour of sun each day for a week.

Keep young seedlings away from wind and prolonged sun exposure during this phase.

From Stem Cuttings

It’s not only the number of seeds it produces that makes purslane such a good spreader.

Each piece of stem can create a new plant, which makes your job as a gardener easier – or more difficult, if you find you can’t keep it under control.

To propagate from stem cuttings, use a sharp knife or scissors to cut a 6-inch-long stem from the parent plant. Remove the leaves from the bottom half.

Plant the stem in potting soil with half of the stem buried underground. Place in an area with bright, indirect light, and keep the soil moist but not waterlogged.

After a week, you should notice your cutting beginning to grow, and it should hold firm in the soil when you give it a gentle tug

At that point, it’s ready to be transplanted.

You can actually get away with cutting 1-inch pieces of the stem and burying them entirely, 1/4 inch deep directly in the garden.

In a few weeks, you’ll start to see new plants popping out of the soil. I’ve yet to have a single cutting fail when I planted them this way.

Still, the first method that I described is the safest way to go.

Transplanting

As you’d expect, this vigorous plant is a piece of cake to transplant.

Dig it up with a trowel, making sure to keep the roots and stems attached. Dig a new hole twice the size of the rootball.

Place the uprooted plant in the hole, setting it no deeper than it was planted previously, and fill the hole back in with dirt.

Keep in mind that unless you dug up the plant entirely, leaving nothing behind, a new one will likely sprout up in its place.

How to Grow

Purslane needs full sun to grow best. That said, if you want to encourage flower production, plant in an area that is partially shaded from the heat of the day.

These plants also like it warm – the more heat, the better. If you have a hot spot next to a brick fence or cement wall where other specimens struggle, put your plants there.

Purslane likes it best when the temperatures are above 70°F, and thrives even when it gets above 100°F.

These plants aren’t picky about soil, as you may have noticed, given the fact that they grow readily in sidewalk cracks and on the side of the road.

For best results, plant in average quality soil that’s well-draining, with a pH between 5.5 and 7.5.

You’ll get larger, juicier plants by growing in loamy, porous soil than you will in compact, poor earth. However, I find plants grown in lower quality ground have a stronger flavor.

When it comes to fertilizing, you have permission to be lazy. Purslane doesn’t need anything, though a bit of compost worked into the soil when planting is never a bad idea.

Watering is another area where you don’t need to overdo it. This heat-loving plant will die if it gets too much water, but providing even and consistent moisture will give you a leafier, more robust harvest.

As you’d expect from a succulent, it’s happiest in dry – but not parched – soil.

To see if your plant has the right amount of moisture, stick your finger into the soil. If it’s dry up to your first knuckle, it’s time to water.

To avoid problems with fungus, water at ground level rather than overhead.

To keep it from taking over your garden, trim the plant back to 2 inches above the soil, or harvest it entirely before it flowers.

Apply an inch of organic mulch, such as wood chips, in midsummer to keep it from spreading.

Mulch slows the spread of purslane by blocking sunlight that’s required for the seeds to germinate, and some types of mulch – like black walnut – contain chemicals that inhibit growth.

You can also grow purslane in containers, where it can thrive quite happily since it doesn’t require daily waterings.

This is a smart way to reduce and help prevent the spread of this plant, however, I’ve even had wild volunteers sprout in my unused containers. Those seeds just want to grow!

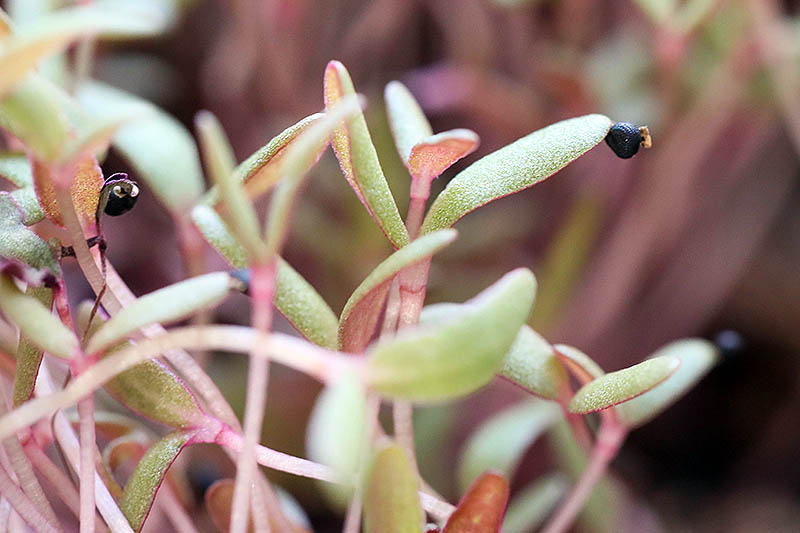

Growing for Microgreens

Purslane microgreens are tart and juicy. I grow them year-round on my windowsill, and because they grow so quickly, I have a constant supply on hand.

Use a seed tray or other flat, wide container, and fill it with potting mix at least 1/2 inch deep.

Sprinkle seeds over the moistened soil and gently press them in. Place in a sunny area where the temperature is consistently about 75°F, or use a heat mat to keep seeds warm.

Keep the soil moist until they sprout, which will take about a week. After that, allow just the surface of the soil to dry out between waterings.

Once the greens emerge from the soil with their first leaves, also known as cotyledons, you can dig in. This typically happens in 14-21 days.

Unlike some other plants, purslane’s embryonic seed leaves are succulent and delicious, so you don’t need to wait for true leaves to develop before you start picking.

I like to pluck my microgreens as I need them, and leave a dozen or so seedlings alone to be transplanted out into the garden for continual harvest when I’m ready.

Growing Tips

- Plant in full sun

- Don’t overwater

- Prune or pull up plants before flowering, to prevent spread

Cultivars to Select

There are dozens of varieties available, but you’ll most commonly see the cultivars ‘Gruner Red’ and ‘Goldberg’ for sale.

Common

The typical garden variety, common purslane (species P. oleracea) grows low along the ground and spreads up to 18 inches once mature.

You can find seeds available from True Leaf Market.

Golden

A cultivar of P. oleracea var. sativa, ‘Golden’ purslane has tender yellow-green leaves and grows to a mature size of about 10 inches tall.

Seeds for ‘Golden’ are available from True Leaf Market.

Goldgelber

P. oleracea ‘Goldgelber’ matures in 26 days, and spreads up to 12 inches wide. It grows to be about 6 inches tall when mature.

You can find ‘Goldgelber’ seeds available from Burpee.

Gruner Red

P. oleracea ‘Gruner Red’ has pink-tinted stems, much like the common purslane you have probably pulled as a weed.

It has thick, oval-shaped, green leaves of about an inch long, and a mature size of up to 12 inches tall.

Managing Pests and Disease

Purslane is a hardy plant. It doesn’t typically attract or succumb to many pests or diseases that you’ll need to battle, though there are a few things to watch out for:

Purslane Blotchmine Sawfly

You may encounter purslane blotchmine sawfly, Schizocerella pilicornis, the leaf-mining larvae of which nibble tunnels through the leaves of plants.

These may leave black or blotchy telltale marks on the leaves, and a severe infestation can destroy an entire crop.

The pale, yellowish larvae burrow underground to pupate, and female adult sawflies emerge in late spring to insert their eggs in the edges of the leaves of plants.

The 1/2-inch-long black or dark-colored adults may be difficult to spot since they typically only live for about a day, and the larvae spend most of their time feeding inside rather than on the surfaces of leaves before they travel down to the ground to burrow in the soil and pupate.

Multiple generations can be produced per year, and purslane is the only host to this insect. It’s often found in hemp fields, since they tend to be full of purslane as well, growing as a weed.

If you do see larvae or evidence that they have been feeding on your plants, remove any bugs that you can by hand, and apply diatomaceous earth around plants.

Leaves with mining damage can be squished between your fingers to kill the larvae, or removed and disposed of as an extra precaution.

You may also want to encourage parasitic wasps to take up residence in your garden – they love to make a snack of these pests.

Portulaca Leafmining Weevil

The larvae of Hypurus bertrandi weevils are tiny leaf-mining grubs that may chew tunnels through the leaves of your plants.

Adults may also cause damage, feeding on the edges and surfaces of leaves as well as the stems and developing seed pods, but this causes only a fraction of the damage that feeding larvae are capable of.

Common purslane is the only known host to this insect.

Similar to the blotchmine sawfly, you can often find it in fruit orchards, another place where P. oleracea often grows as a weed.

You can use a targeted insecticide like Spinosad to control them. Apply it at night, when the bugs are most active.

You can also encourage parasitic wasps like Diglyphus isaea to come to the area and take care of them for you.

Fungus

Just about the only disease this plant struggles with is black stem rot, caused by the fungus Dichotomophthora portulacae.

This infection typically only happens if you overwater your plants or live in a moist climate. You’ll notice black lesions on the stems that may spread to the leaves.

You can use a sulfur or copper-based fungicide if the disease starts to spread to the leaves.

I find that a regular application of neem oil will take care of a mild case of fungus that only causes a few small spots on the stems.

Harvest

You can expect to harvest mature leaves about 50 days after you plant your seeds.

The time of day that you harvest the plant will impact its flavor. In the morning, the plants contain more malic acid, making the leaves taste more tart.

In the evening, they contain less of this acid and are a bit sweeter. Experiment to see what you prefer.

To harvest, snip a section of the plant with sharp scissors and immediately put it in a cool spot.

You can harvest a single stem at a time and it will regrow.

Or, you can harvest as much of the plant as you want at a time, so long as you leave about 2 inches of the plant growing above the soil, and it will come back as long as it’s warm enough.

When I’m making a big salad, I’ll go outside with a pair of scissors and trim the entire plant, leaving several inches at the base to regrow.

As a result of its robust growth habit, you can expect about 3 harvests per year from each plant that you grow.

Preservation

You can store the leaves and stems wrapped in a cotton cloth or in a plastic bag in the refrigerator crisper drawer for up to a week.

They can last a few days longer if you don’t wash them first before tossing them in the fridge.

If you don’t plan to use your greens right away – which happened to me when I decided to tackle a particularly large patch of the wild variety in my garden one year – you can also dry them.

Dried purslane acts as a thickening agent that you can use in soups or desserts.

Because they have so much water in them, it’s best to pluck the leaves off the stems and lay them in a single layer on a rack or cookie sheet.

Then, using a food dehydrator or oven set to 135°F, dry them until they’re brittle.

At this point, you can use them as a dried herb in your cooking, or blend them up to make a powder to add to soups and smoothies.

Nutrition

Many types of fish contain high levels of healthy omega-3s. But fish can be expensive, and some types of fishing have a negative impact on the environment.

Purslane, on the other hand, contains the omega-3 fatty acids alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) and gamma-linolenic acid (LNA), with 4 milligrams of these per gram of fresh leaves.

Grow your own purslane and that can add up to a significant cost savings for your wallet, and for the planet! P. oleracea actually has more omega-3s than any other edible green plant.

While the juicy leaves and stems contain mostly water, it’s also rich in vitamins A and C, as well as magnesium, iron, and potassium.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

This veggie has a mild enough flavor when fresh that it pairs well with a variety of ingredients, from lettuce, tomatoes, and cucumbers to eggs and fish.

I adore pickled purslane.

To make a quick pickle, just chop the leaves and fill a jar.

Bring your choice of vinegar brine to a boil (I like a mixture of apple cider vinegar, water, sugar, and pickling spices), and pour it over the leaves to cover.

Screw the lid on tightly, and refrigerate for about a week before using.

The leaves are delicious tossed in potato salad, or layered on open-faced mackerel sandwiches.

I also like to add handfuls of fresh or sauteed leaves to soups just before serving. I find chilled cucumber purslane soup to be particularly refreshing when it’s hot out.

In the summer, you could also try stuffing trout with fresh purslane leaves before roasting in the oven with butter and lemon.

In the middle of the winter, when my purslane microgreens are just about the only fresh thing growing around the house, I like to add them to a grain salad with pomegranate seeds and cooked barley.

My best advice when using purslane in your kitchen is to either eat it raw, or cook it completely. If you only partially roast or boil it, it takes on a slimy texture, similar to okra.

Medicinal Uses

Purslane has been touted throughout history for its medicinal qualities.

Today, there’s some evidence that it can help to reduce uterine bleeding. When eaten regularly by people with diabetes, an improvement in serum insulin levels was noted in one study.

A small clinical trial found improvement in pulmonary function when purslane was used to treat asthma.

And a study published in the Journal of Ethnopharmacology in December 2000 by K. Chan, et al., indicated that it’s useful when used topically as an anti-inflammatory.

It can also hasten wound healing, according to another study published in the Journal of Ethnopharmacology in October 2003 by A.N. Rashed, F.U. Afifi, and A.M. Disi.

At my house, I like to steep the dried leaves in olive oil for several days to make a salve, and then apply it topically as needed when my skin is irritated from the winter cold or summer heat.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

It Doesn’t Get Any Easier Than Growing Purslane

A lot of herbs and veggies lay claim to being easy to grow, but purslane might be the king of care-free gardening.

Your biggest challenge will likely be using up your harvest, and stopping it from spreading throughout the rest of your garden.

Now that you have the knowledge necessary to make the most of this nutritional powerhouse, hopefully you won’t toss them out next time you come across a patch of these “weeds” in your yard.

Be sure to let me know your favorite methods for prepping purslane in the comments below – I’m always looking for ways to add it to my kitchen table.

Looking for even more medicinal plants to grow in your garden? Check out these articles next:

- The Many Uses and Benefits of Yarrow: A Healing Herb

- How to Plant and Grow Plantain, A Culinary and Medicinal Herb

- A Medicinal and Visual Delight: How to Grow Feverfew

Photos by Kristine Lofgren © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photos via Burpee and True Leaf Market. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. With additional writing and editing by Allison Sidhu.

The staff at Gardener’s Path are not medical professionals and this article should not be construed as medical advice intended to assess, diagnose, prescribe, or promise cure. Gardener’s Path and Ask the Experts, LLC assume no liability for the use or misuse of the material presented above. Always consult with a medical professional before changing your diet or using plant-based remedies or supplements for health and wellness.

The post How to Plant and Grow Purslane appeared first on Gardener's Path.